Picture: Adobe Stock

In recent weeks, Disney shared for the first time a tangible number for one of its series: “14 million views for the first episode of Ahsoka” and “16 million views” for The Little Mermaid. Soon enough, some analysts and media pundits railed against that number, calling it “useless,” “worthless,” or “opaque,” even though the methodology behind it is quite transparent: Disney took the total hours viewed of the first episode of “Ahsoka” from Tuesday to Sunday and divided it by its runtime. Hence, 14 million views. It did the same for “The Little Mermaid” over its first five days of release on Disney+ globally.

If you read What’s On Netflix, you know that it’s the exact same methodology Netflix now uses for its Top 10 and one we’ve been using for even longer, called CVE (or Complete viewing equivalent), in our streaming reports.

There’s value in this metric, but in order to understand that value, we need to take a closer look at how ratings are usually counted.

How are ratings usually counted?

In France, TV ratings are shared by a company called Mediametrie.

They do not deal with streaming yet, but the methodology they use for linear ratings is interesting in its own right and relevant for streaming. Every day, they release the ratings for each program. Let’s say a film was broadcast in prime time yesterday on France 2, one of the biggest TV channels here. This morning, Mediamétrie will share that 1.6 million people watched it. This number does not mean that 1.6 million people stayed from the beginning until the end of the movie, though. It’s an average that takes into account the people present at the beginning, people who arrived midway, and left at some other points. In fact, this is a real example, and I have real numbers from Mediamétrie. 2 million people were watching at the beginning of the film, 1.5 million were here 80% into the film, 0.868 million were here 90% into the film, 0.272 million were still here 98% into the film, and finally, only 0.144 million watched it from start to finish. Based on this fluid viewership, Mediametrie comes up with an average: 1.6 million viewers.

It’s a convenient number, easy to share and compare to other programs, even if more people were here at the beginning of the film and less were still here at the end. If you only count people who stayed for 10 seconds, you get 6.9 million people. One film broadcast on linear and dozens of viewing data points that could possibly be shared, from starters to completers, but the one that sticks, the one that is commonly used and accepted by broadcasters and ad agencies, is an average.

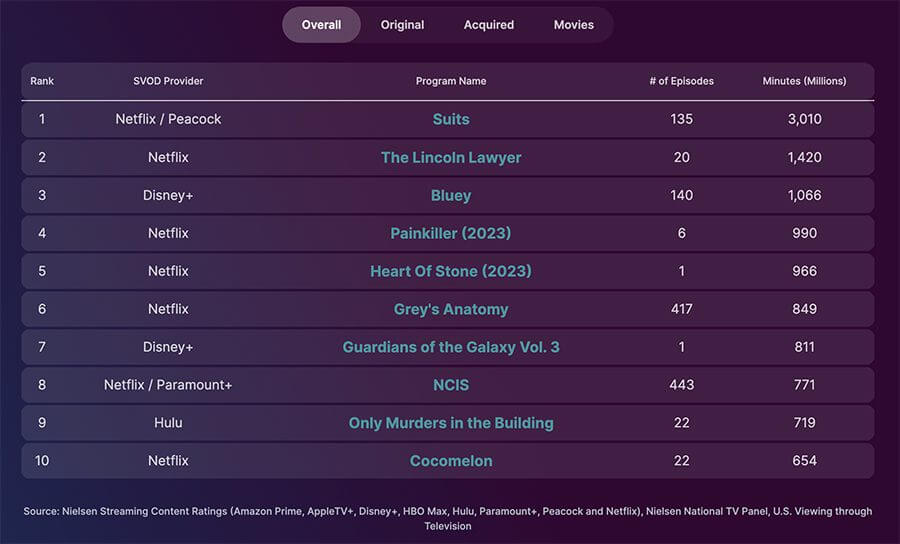

That’s for linear. In the US, for its streaming Top 10, Nielsen is also pretty transparent about its methodology. Based on a panel of viewers, Nielsen extracts the average number of viewers for each minute of a program available on streaming during a given period of time (from Monday to Sunday), calculates the average over the duration of the program, and multiplies it by the runtime of the program. That’s how Nielsen comes up with an audience metric based on minutes viewed. But the important part is it is also an average based on total viewings.

Nielsen top 10 example

In a nutshell, Médiamétrie? An average based on total viewings. Nielsen? An average based on total viewings. Netflix and Disney? An average based on total viewings.

It is not unexpected to see an alignment of methodologies as Netflix and Disney are pushing harder into ad-supported subscription tiers, and by doing so, they need a common language with ad agencies, one that is already used by institutes such as Nielsen, for instance.

There are a few caveats to keep in mind, however.

First, the number of viewers for a series or film released on streaming will never be higher than the one of its first minute. Every following minute will see a decaying number of viewers (more or less important) as people stop watching for various reasons. That is especially true in streaming, as there’s no linear effect with which you could stumble upon an episode or a film midway through. Programs usually start from the first minute. That’s why Netflix used to share in the beginning the number of paid accounts that started a program for at least two minutes (the first two minutes in general) since it was the highest number they could get on that particular program. It was a metric that focused on reach more than viewing.

Second is that the first episode of a series released on streaming will usually also be the one with the highest number of viewers of a whole season or even a whole series. That’s why Disney decided to share the number of 14 million CVEs for the first episode of Ahsoka only and not the number of CVEs for the first two episodes of Ahsoka, even if they were released on the same day because the average number of views for the second episode had to be lower than the one of the first episode—there’s no point for Disney in sharing that number in a press release.

The perfect audience metric in streaming does not exist

Which “better” metric could be shared by streamers? The problem is that there are not many to go around, and the ones streamers might share all have flaws and blind spots.

Number of viewers?

That’s impossible to know.

Streamers can’t know how many viewers exactly are watching their content. They know the number of paid accounts or even profiles, sure, but are those paid accounts or profiles used by one person or a whole family of twelve? They could extrapolate a guess based on the number of accounts, but would that be a fair representation of the number of “actual” viewers? Sometimes, I like to watch stuff alone, and some other times, I watch stuff with my wife and my kid, all on the same account and profile.

Number of accounts?

It’s already been done by Netflix publicly circa 2018-2020, and they got criticized for it as it was a number with huge blindspots for the reasons explained above. It should be noted, however, that when dealing with creators (in certain countries, it seems), Netflix still shares the numbers of accounts that started and finished a program based on the starter and completers metric they used to share publicly a few years ago. So, it could make a comeback at some point in the future.

Number of clicks on “play”?

That’s a metric used in France by Netflix to pay residuals to authors per a local agreement. No completion is needed; just count the clicks on “play,” even if it’s a repeated viewing.

This metric would be like a “tasters” number, people who started shows or films. It’s not entirely worthless, but not the whole picture either.

Number of accounts who finished a series or a film?

What does “finish” mean here? As you can see from the example of the film on French linear TV I shared above, the rate of people still watching 90% or 98% into the film is definitely not the same. So, which threshold do we use? Just right before the closing titles? At the very end of the closing titles? Accounts who watched 70% of the film, like Netflix used to share a few years ago? But that metric, too, was derided because of the “but what about people who stop watching 71% into the film?”. And do you count people who stopped watching a film or a series because their kids started crying during their nap and had to check on them, only to return to watch the film or series a week later? (This is not a hypothetical example if you were wondering).

External demand?

Actors via SAG-AFTRA are floating the idea of a “demand” metric used by data firm Parrot Analytics, but that one, too, has flaws too big to ignore.

For starters, it does not remotely reflect actual viewing happening on the various streaming services since it’s using global piracy viewing as a major factor for their metric, not legal viewing. Plus, it does take into account online “noise” on social media websites and other user-generated websites, regardless of the “content” of the online discourse. All the factors baked in that demand factor are circumstantial and not directly based on actual viewing figures from audience panels or other sources that might be less prone to skew or bias.

Right now in the US, authors and actors are asking for more data transparency on streaming, and that’s an understandable claim. But every – and any – number shared by streamers would be without context since it would only relate to the series or films from said creators, and with methodological blindspots. It’s not like Netflix would use the numbers of Stranger Things 4 as a standard comparison for all the numbers they would share with creators of other series. They could do an average among films and series of the same genre or geographical origin though.

And that’s where I circle back to the “views” metric or CVEs, if you will, shared by Netflix more or less since June 2021 and since last week by Disney. Here’s a metric with a clear methodology that can actually be compared across streaming services, even though it won’t answer questions about retention or decay rate. The only problem with it is maybe that it is called “views” by Disney and Netflix when it is not. This terminology is misleading, and it probably should be called “Complete Viewing Equivalent,” which they are.

Precision and terminology matter when it comes to streaming ratings.

Picture: Disney / Star Wars

The first episode of Ahsoka was watched the equivalent of 14 million times over its first five days. The whole season of One Piece was watched the equivalent of 18.5 million times over its first four days. A worthless metric? Only if you don’t pay attention to what those numbers are, what they mean, and, more importantly, what they don’t mean.

In the comments, feel free to react to this piece and tell us: If you were to sell a series or a film to a streamer, which metric they have would you want to know?