Pictured: Brett W. Bachman

The Fall of the House of Usher marked the end of Mike Flanagan’s time at Netflix. What’s on Netflix recently had the opportunity to interview Brett W. Bachman, the editor of The Fall of the House of Usher.

The Fall of the House of Usher is the fifth Netflix Original series created by Mike Flanagan and the last released under his exclusive output deal with the streaming service.

Before working on The Fall of the House of Usher, Brett W. Bachman worked on movies such as Cooties, Mandy, The Vigil, Pig, V/H/S/94, Pig, and Next Exit.

How did you become involved with The Fall of the House of Usher?

Brett: Great question. A bit of a backstory: Mike Flanagan offered me the job on Twitter. It was a direct Twitter DM he sent me. I’ve been a fan of his ever since 2013 with Oculus, and I remember driving around in my car one day, and there was an interview he was doing. They were centering this interview around an editor-turned-writer and director, and I thought that was cool. I thought this guy had come up through the ranks of reality TV and unscripted, and now he’s directing a pretty renowned horror feature that received a lot of acclaim. It was just really cool.

We’d run in similar circles in the last few years, and I’d worked with a few of his collaborators before, Karen Gillan and Molly Ulfman, on their respective features. They both worked with him on a few of his early films. I’m also friends with some producers from Spectrevision, Elijah Wood and Daniel Noah, who are pretty close with Mike. There was a bit of a vetting process, which I guess was happening behind the scenes. It all came up to this movie I did a few years ago called Pig, which Mike was a gigantic fan of.

I think he might have been our biggest fan. I believe he’s seen the film four or five times already. It became a thing with him when they were shooting Midnight Mass or might have even been Midnight Club, where if someone on the crew or cast had admitted that they had not seen this movie, he would plop them down in front of a TV screen and watch them watch the film.

He had a general with my director from that meeting, Michael Cernovsky, and I got a text from Michael a few days later saying that Mr. Flanagan might be reaching out to you. Hence the DM message on Twitter where he said, “I’m a big fan of your work. As another editor, when I see films that I appreciate the craftsmanship, I keep looking up who did it, and I’ve looked you up a few times by coincidence. Would you ever be interested in coming aboard to the television world?” I think I said something like I don’t care what medium it is. It could be a TV show, a music video, a commercial, a short film, or whatever you’re doing; I’d be happy to do as a fan. That’s kind of how I got into the crew and how I got brought in.

Jacob: I’ve been a fan of Mike Flanagan for a long time, too. I’ve watched everything he’s developed for Netflix so far. I don’t think anyone out there is as good at adapting gothic horror as Mike Flanagan.

Brett: Yeah, I would fully agree. I love his sensibility of balancing humanistic stories of flawed characters and examining their psyches but doing so through a genre lens doing so in a format that allows you to play around with mood and ambiance. The guy does some of the best jump scares I’ve ever seen before, but wrapped around really engrossing human stories. I don’t know anyone else that’s kind of working on that same level right now. I think the great irony is that I think he’s so good at them [jumpscares]. But he also hates them as well.

I’m assuming your audience may know about the Midnight Club? When he did the previous series, executives told him to keep adding more of these jumpscares despite how much he hated them. So he wrote a scene specifically to break the Guinness Book of World Records, and so he could have a little plaque that said, I’ve done the most amount of jump scares in any scene before, so I am the expert on it, so I can tell you this scene does not need any more.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK – OCTOBER 06: Andrew Glass of Guinness World Records awards Mike Flanagan onstage during Netflix’s The Midnight Club at New York Comic Con on October 06, 2022 in New York City. (Photo by Jason Mendez/Getty Images for Netflix)

Jacob: That scene makes a lot more sense now.

Brett: Like I said, the irony is that he’s so good at them when he decides to do them. My wife has never been a big horror fan, and it wasn’t really until I showed her behind the scenes on some of these set pieces that I think she got an understanding and a love of the craft. One of the ones that she became obsessed with was one from Oculus. It’s one of the moments where the child comes in front of a mirror, and she sees a reflection of the creature behind her and shoves this entity possessing her by shoving his hand into this girl’s mouth. We just watched this scene on loop four times as I was describing why he’s doing this and this is why he’s returning here. This is how he’s teasing her with the sound. And again, he’s so good at it, but I think he would be quick to tell you that he doesn’t particularly love doing them again and again. I think he would much more be inclined to examine, personal trauma. I think he’s responding. You can see that in his work in the last few years, whether it be Usher or specifically Midnight Mass, his interest in delving into very deep, personal human stories and asking the audience to build a sense of empathy and connection with some flawed characters.

Picture: Mike Flanagan working on the set of The Midnight Club – Intrepid Pictures

What was it like working with Mike Flanagan for the first time?

Brett: He’s honestly the dream collaborator. He’s really receptive. He’s very kind. I remember being very nervous because I’ve been a big fan for years, close to a decade even, and our first meeting wasn’t until we were beginning the director’s cut in Burbank, like, after they had wrapped Usher. But I had the opportunity to talk to him a few times during set when they were still shooting. What struck me immediately was how excited he was for this particular series because it would deviate from the others. He was so excited about making something that felt like it would be a romp. He kept on using a rock and roll show as his word.

He felt that if the other shows had been more of a ballet or a classical opera-like, the analogy for this is that it was going to be a rock concert. He mentioned a lot about wanting to have this unrelenting pace, these tonal pivots that he’s never tried before, and centering the entire idea of the story around a karmic fantasy about really despicable people getting essentially what’s coming to them and how much he’d been dreaming that the world operated on some kind of grand karmic scale. And it doesn’t. He wanted the bad guys to lose. So, I think he enjoyed writing, editing, and directing a show where the sense of karmic justice gets dealt out.

As much as we center the entire show on the ushers, we ask the audience to follow these individuals and hopefully connect with them. Even if they are despicable, you get a sense that they are just morally corrupt and keep making the wrong choices. But at the end of the day, he wants you rooting for the paranormal entity that is the executor of fate for all these folks.

In terms of working with him specifically, working from editor to editor, he’s a dream collaborator because he can be so specific with a lot of his feedback. As a film editor, a lot of what I usually operate with, with directors or producers is a sense of sitting down at a computer together and trying to understand each other’s language and intent. If I get a note, a lot of times, we talk about the note for five to ten minutes so that I feel like I get a clear understanding of what they want. Mike is very concise with his communication and possesses editors because he is an editor.

So, he still thinks of himself as an editor first. Instead of saying something about this jump scare or something about this timing or something about this particular scene not working just right, he will give you very, very concrete information from an editorial perspective about why it isn’t working for him. You’ll get as precise as it’s two frames off, or the eye line is incorrect. You need to go to this other take that’s slightly a few more degrees like that. Or, in terms of tempo or pace, it’s like there’s some air in the scene because the music isn’t loud enough. So, if you bump it up by four or five decibels, it’ll have a completely different feel. He can be that precise in his feedback because he does the same thing I do. So it’s wonderful that you feel it can be those decisions, and those discoveries can be made very fast. It allows everybody in editorial to operate much faster than I’m typically used to. So we get approvals out the door much quicker. Mike is happy right away because there’s no guessing game, and everything runs quickly and efficiently with him. He’s also incredibly smart. He wants to see scenes where, if I’ve edited them, there’s a sense of intent, a point of view already there. He loves to see scenes that are relatively close to being fully developed and polished. So, I do a lot of sound work. We do a fair amount of work on presenting the scene as close to his finished as possible for him. So hopefully, when he comes down, and he sits, and watches a cut with me, you know, maybe he has less than 15 notes for an hour-long show.

Pictured: Samantha Sloyan as Tamarlane Usher – Intrepid Pictures

Jacob: That’s helped to answer a follow-up question I had. As you’ve described Mike as a dream collaborator, I was going to ask if he had a specific vision for the series and how much freedom were you given to experiment?

Brett: Mike definitely had a specific vision for it. He said wanted this to be very different from his previous series. He wanted the audience to have a lot of fun with it. I think he was inspired by Diallo, by Italian slashers.

You can see that in a lot of the visual style. He had a desire to make an Edgar Allan Poe show for a very long time, and I think the thing he and his writing partner and his producing partner, Trevor Macy, found as they were looking at a lot of the material was that Poe was really funny. He had this dark, macabre sense of humor, and I think Mike wanted to pivot from a lot of stuff he’d been doing recently. But I know the more he looked at Poe, he was like, this is a story of capitalism and decay and for social critique.

He wanted to have fun with it, and he wanted it to have a sense of snappiness and comedic timing that I think would surprise many people. It surprised me when I first read the script because I was expecting much more Crimson Peak, Hill House, or something dripping with period imagery. After all, I think we all associate Poe with a particular visual language.

Pictured: The Usher Family – Intrepid Pictures

So I think it was page two, discovering this was taking place in the modern day really set this apart quite quickly for me and constantly surprised me about where the direction of the show was going. I think the most significant departure for me was how I’ve become so enraptured with many of his characters in his previous shows, how you get a sense of endearment to them whether it be on Hill House or Bly. You’re following relatable characters and want to root for them.

This is a show where the characters are all pretty horribly reprehensible for the most part, with a few key outliers. The central Usher family comprises individuals most would be repulsed by and wouldn’t want to be friends with. So the biggest, the creative direction of the show, and one of the biggest challenges for me going into it was how we could trust the audience would want to follow a story about characters that are just as despicable as this. How can you ask them to create a sense of empathy for these individuals? If you talk to most writers, they would have a feeling that even though they’re flawed characters, there are still parts of myself in them that I see.

I think many writers would say that they enjoy writing bad characters because they jump on their worst impulses or maybe the sense of id, the sense of their selfishness. So I began to kind of look at the characters in the same way where I started to see them as examples of my own worst tendencies kind of gone awry if I didn’t have that superego or the little angel on my shoulder telling me no, you shouldn’t do this, this is very bad. So I think the actor certainly relishes as well. And there’s an excellent opportunity where they [the characters] can do the right thing, say the selfless thing, or make a morally just decision. But these individuals fail because they just keep on choosing the selfish path. They keep choosing something that will only serve their best interest. There’s a great moment in episode six with Samantha Sloyan and Ruth Codd where Sam, as the Tamerlane character, walks into her dad’s house looking for him and finds her stepmother there, who says that this is so screwed up, all these deaths, all this tragedy. And it feels like this is when families usually come together, and this is, we’ve never been farther apart than ever. And there’s something that Sam does, which I love so much. Even in the script, Mike wrote that Tamerlane is fighting against this emotion. She’s fighting back against this, this tendency to want to comfort, and you see her shut that down. You see her repress it and push it back. And then she just says, tell him I swung by, and then she leaves.

I love that the show has these opportunities; you see them constantly choosing the path of selfishness, greed, and corruption. So, as much as they are despicable, I want to find little moments where you wonder if they could go the other way. And they never do, of course not. It wouldn’t be the same show if they did. But I think that’s how I approach the creative direction and kind of the biggest challenge for me, to be honest, over the entire show.

Jacob: I liked what you said about the Usher children and how irresponsible they are. Even Leo, who just wanted to make video games and take drugs, represents Sloth.

Brett: what I like about Rahul’s take on that and the Leo character as well is that you see genuine moments. In episode two, for instance, Perry is over at his house, saying that if I throw this party and print six figures, I might get some respect. Rahul [as Leo] reaches out, and he’s like, you’re better than this. You’re better than a drug dealer. And you’re like, holy shit, is this like a sincere moment between brothers that they’re having? He’s like the one Usher who is almost redeemable. He loves his siblings, and you see how he reacts when Camille dies. He has the most normal reaction to all of this trauma going on, and yet he’s still reprehensible as he cheats on his boyfriend and wants to break up with him simply because he won’t let him take all these recreational drugs. He’s still not a good person to be friends with, but there are traits that make him three-dimensional.

Picture: Rahul Kohli as Leo Usher – Intrepid Pictures

Jacob: I find it telling that the less influence Roderick had on the children, the further they stood apart from him. I believe it’s mentioned that Leo wasn’t introduced to the family until he was 18, whereas Tamerlane and Frederick were with him from day dot and were arguably two of the worst of the family.

Brett: That’s a great way of putting it. I hadn’t thought of it like that before specifically, but tracing all the characters’ paths, I think you can make a compelling argument for that. You certainly see that everything they’re doing is a reaction to either his influence or his lack of influence, his lack of giving them fatherly love, but in a sense, you shouldn’t need to compete with your siblings for attention and fulfillment. And yet they constantly do.

Jacob: In the end, it all makes sense why he wasn’t such a great father because they were all doomed. There’s almost a disconnect between him and his children when he knows that they’re doomed to die.

Brett: I had thought about that while editing the show as well. We played with this thing in the editorial and something we were conscious of: How much do we believe modern-day adult Roderick and adult Madeline remember this thing in 1979? Does Roderick believe this deal? Does he recall this? Or did he? It’s like in episode eight when he says it was a folie à deux, like this is a shared dream we had. Where I tend to come down on it, which could differ from Mike, the writers on the series, or from the actors that portrayed them. I always felt like Madeline was a bit more sharper of the duo.

I always think that she understood what this thing was deep down. I think that’s ultimately why she didn’t have a family. I think that’s why she, I think she mentioned this in her monologue in episode eight, why she had forms of contraception throughout her life. I think Roderick was not necessarily more in denial about the entire thing, but he was more blase about the whole thing. I think it just shows the root of the lack of his morals where even if he was repressing this or in denial about it, he still went off, and he had all these kids because it was only ever going to be about him. As he says, I will ascend these heights on a tower of corpses.

I think that certainly applies to his own children as well. I think it speaks a lot to this guy. This character’s sense of evil is that everything is disposable for him. He’ll do whatever it takes to get what he perceives as his birthright, which is apparently unlimited money and power. Like he says to Dupin, it’s never enough. There’s never a figure where he’d be like, I’ve made enough money.

Picture: Bruce Greenwood as Roderick Usher

Jacob: In contrast, I thought it was a very beautiful moment between Verma and Lenore just before her death—that beautiful monologue, describing to her that one action she took had such a significant ripple effect. Of all the horror in the show, there’s still time taken to acknowledge there is still some good in the world.

Brett: I got to tell you, I cried watching dailies for that scene. I cried the first time I cut that scene. And I called in the sound mix after watching that particular scene 40, 50 times over the course of a year and a half. It’s one of my favorites in the entire show. Kylie and Carla are just phenomenal in it, both together.

I love Michael Famigliari, RDP and director for that episode. I love the way he places the camera. So, by the end of that scene, they’re both spiking the lens, and you sense this intimate, personal connection between them. And it’s so flummoxing as well. Carla, who we’ve so associated with this bringer of justice and karma, really does feel, I think, quite devastated by doing this. I think she certainly has a sense of compassion and curiosity for humans. She’s not just deaf. There’s something else with her going on. And I also told Mike this in the sound mix, that I think that particular scene embodies these thematic elements in the show, which I believe are all throughout the subtext.

Something we don’t specifically shout out where you look at characters like Roderick, and you look at Madeline. And one of the driving things I think they’re so focused on is this idea of the pursuit of immortality. Madeline is doing it through her AI and this technology component. Then Roderick does it with the company, building this empire and this company, making this all his legacy. What I love about that particular scene with Carla and Lenore is that that entire scene is about legacy. It’s about how this butterfly effect of you doing the right thing, the just thing, the compassionate thing, by saving your mother, but standing up to your father by standing up to evil, that little microscopic thing that in the greater sphere of the world had this beautiful ripple effect where it went on to affect her life directly, which I’m going to butcher the quote of it. Still, it went on to then, the first year of this foundation, dozens and then hundreds and then thousands and then too many to count.

So, in a sense, Lenore’s legacy is that she achieves this almost sense of immortality by this good deed that just rippled throughout the cosmos. It has touched so many more lives, arguably as many lives as the evil that Roderick and Madeline had. But I think it shows just the tenderness that Mike and the writers have for these characters and how I think this particular show did such an excellent job at balancing its tones of, yes, it’s fun. They’re reprehensible characters, but to have all that work, you must also have the other side.

Picture: Bruce Greenwood as Roderick (left) and Kyleigh Curran as Lenore right – Intrepid Pictures

You have to have the people that stand up to evil, whether Lenore, Dupin, or Annabelle Lee; you have to have the other side of the characters you want to root for. And unfortunately, it seems like most of them get stomped on in this particular show.

Jacob: What’s interesting is what you said there, with Lenore, that one act of good completely outweighed on the scales what eight members of her family couldn’t do in a lifetime. And she was only a teenager.

Brett: Yeah, exactly. How do I respond to that? No, I’m like, is there a question? But no, I agree. Lenore is one of my favorites. Lenore is, I think, fascinating in the context of the show. She is someone, if you’re familiar with Poe at all, believe from the get-go that you’re going to know that she will bite it. There’s something in store for her.

What I found interesting about looking at some fan feedback and looking at some things that fans have written, is how many of them wanted Lenore to survive on some kind of technicality. I heard a lot of theories where they were like, well, Lenore’s not Frederick’s real daughter. She came in from another marriage. She’s Maury’s daughter from another husband or something like that. How much they wanted her, how much they loved her, and how much they wanted her to survive. Because she’s one of the rare characters that survives to episode eight that you’re rooting for.

The show wouldn’t work without her passing away. She’s one of the rare victims from Verna, where you feel like it’s the character we’ve gotten to know so well. This is the representative of this deal they made of how devoid of responsibility Roderick and Madeline were. That death needs to hurt to have the critique and social themes Mike and company are going for.

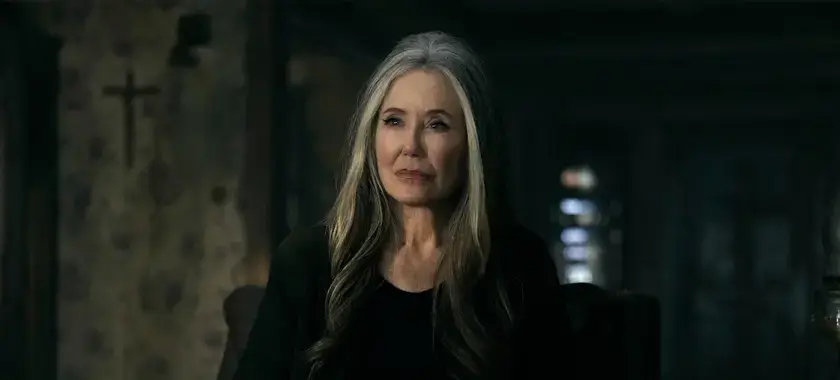

Picture: Mary McDonnell as Madeline Usher – Intrepid Pictures

Jacob: It’s ironic, because even though her death probably hit the hardest, it was the most peaceful. Everyone suffered in their deaths, whereas she was slowly put to sleep.

Brett: Yeah, it was beautiful.

Were you already familiar with the work of Edgar Allan Poe? Or was the series a pathway to learning more about the Gothic poet?

Brett: Oh, a bit of both, to be honest. I mean, I think everybody kind of growing up in the American school system has a sense of the legacy of Edgar Allan Poe even if it’s just reading The Raven and the Telltale Heart, you know, in your high school literature classes. I had certainly not known many of his bigger stories, a lot of the smaller stories and the bigger ones.

I’d never read Fall of the House of Usher until this. I had never read William Wilson. I was not familiar with Arthur Gordon Pym—even DuPont, who was like the original detective, even before Sherlock Holmes.

Picture: Carl Lumbly as C. Auguste Dupin (left) – Intrepid Pictures

He was the original guy going in and deducting crimes. I tried to do a little bit of a deep dive when I was brought on because I wanted to have a sense of the legacy I was stepping into with these stories. You never know what little bits of inspiration can hit you if you’re familiar with the source material.

I think the thing that really shocked me was just how deep Mike and his writers had gone into extracting these stories. I mean, so there’s so many. I think there’s got to be like 20 or 30 specific references, you know, and down to some poetry. I’m not Sitting in the Sea, Annabelle Lee, the Raven, of course, but some more obscure works like William Wilson, all the Tamerlane episode, you know, William T. Wilson was Bill T. Wilson in the show is something that was directly pulled from the story. I had a really fun time like purchasing a book from Barnes & Noble the day after I was hired and going through the stories and catching up on the literature. And I still to this day have no idea how they were able to kind of weave so many of these specific characters and callouts and story threads into this overarching narrative.

It’s really a mastery of this web they’ve spun is quite masterful. And I’ve never seen anything quite like it before.

Picture: Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), the father of the Horror genre.

Jacob: When compared to Hill House and Blyth Manor, which are just one book each, you’ve got an entire collection of stories and poems woven into The Fall of the House of Usher.

Brett: One of my favorite decisions they made was to make Roderick kind of into a pro analog character. So the Annabelle Lee poem, for instance, I don’t know if it’s the entire poem that is told throughout the course of the series, it might be. But how it’s the way it’s structured is that every single time he recites this poem, there’s like just a few little stanzas of it, like a few little lines.

I think episode two is the first time that we hear it. I think we hear it again in like episode four. And then by the time you get to episode eight, he’s recited the entire poem that kind of tracks the journey of his infatuation with his wife, his love for his partner. Then the eventual last time we see Annabelle Lee, it’s this really heartbreaking scene of her indicting him and basically saying there’s nothing in you. You are completely devoid and corrupt, and you’re not the man I met, and you’re just empty.

With Roderick reciting the last line of that. I love that it was a way to kind of access this main character’s inner humanity, even if that eventually gets crushed throughout the entire way. I think it really shows him to be a lot more three-dimensional and a lot more tragic than I think his surface would reveal.

You edited seven of the eight episodes, while Mike edited the first; why is that?

Brett: Yeah, well, when I first got hired, my expectation is that I would be editing the first cut of the entire show. So I was the only editor hired on board the project. The idea was that I would be receiving material from the shootup in Vancouver or based here in Los Angeles.

So for several months, I would be editing material. I would be watching all the material that would be coming in and I would be cutting it. Then there are two directors on the show, Mike Flanagan and Michael Fibonari.

The idea was that, so out of these eight episodes, I would have first cuts for everything. Mike would then take the four cuts that I had prepared for him of the episodes that he directed. Mike would take those episodes and then basically kind of run with them and change whatever he wanted. Then I would take the four episodes that Michael Fibonari had directed. And my job from there would be to do the director’s cuts with Michael and basically take a few months to kind of get those into a shape where he wants to present those to Mike and Trevor and the Netflix and say, here are my director’s cuts.

WEST HOLLYWOOD, CALIFORNIA – SEPTEMBER 13: (L-R) Trevor Macy and Mike Flanagan attend the “Midnight Mass” Special Screening Hosted By Mike Flanagan And Trevor Macy at San Vicente Bungalows on September 13, 2021 in West Hollywood, California. (Photo by Rachel Murray/Getty Images for Netflix)

That’s basically what happened when they came back. I gave Mike half the series, took the other half, and worked with Femi for several months. This wonderful thing kept happening where I would be editing, and Mike would come over and knock on my door, saying, dude, great work on two, or like, great job on this. Like, I’m not going to change a thing. That’s phenomenal.

I remember one day, one of my happiest days, I was at work. Mike came by, knocked on the door, opened my edit bay, and said, “So I just got done watching the end of episode two. I’m not going to change a frame.” And I’m like, what? He says so basically from the point that Perry leaves Verna’s room where he meets Verna, and Verna says you are a consequence, and she gives him a little peck on the cheek and then leaves the room. Mike was like, I’m not going to change a frame. So what is in the show right now for Perry going back into the party, Verna warning the guests and the bartenders leaving, and the acid rain. Aside from the final sound, visual effects, and sound mix, the edit is the assembly edit. That’s the first cut that we did.

A lot of things happen that way where we would make Mike make a few changes, and indeed, there are things in episode two and episodes five and six that Mike came in, and he was like, we don’t need that. I can recut that. That doesn’t quite work as well as I wanted to. And he recut things, whatever he saw fit. But what I found pleasurable and one of the things I was most proud of is that after a few months of me doing director’s cut with Femi and Mike recutting his other four episodes, he was like, honestly, I didn’t change that much.

Like he kept so much of these initial assemblies and so much of the work intact that I got a call one day from Nancy Gerhofer, our post producer, and she was like, Mike has given you shared credit on almost the entire series, which I was really, I felt really, really humble and really gratified and very proud of. But after, of course, after we did the director’s cut and got back into the sound mix process and visual effects, we treated the show like an eight-hour movie. So, I was doing visual effects reviews on things Mike had directed.

I was doing sound mix notes and music notes on all episodes. At that point, it’s just a co-editing team, Mike and I divvying up work on the entire series, ushering the whole thing through post-production.

I’m so happy with the show. I’m so proud of how it found a big audience, and yet it’s something I think is so surprising to many people.

It certainly was surprising to me. I was not expecting a modern-day satire of capitalism in an Edgar Allan Poe show. Because it found a vast audience while being original and authentic to itself, I think it’s a show that people would be revisiting for a very long time, and I’m very happy to have been invited to be part of it.

Did you enjoy The Fall of the House of Usher? Let us know in the comments below!